On the Hercules flight that brought us up here from NY, back in late April, Chris belted through my ear plugs, “I GOT IT, I GOT A NAME FOR THE TRAVERSE…”

Amid all the preparations, construction of electrical components, route planning, gear acquisition, conference calling, emailing, etc. we hadn’t yet settled on a title to call this whole affair.

In what would turn out to be our patented style as a field team, the best work came spontaneously, off-the-cuff, and in the moment the demand arrived… Later that evening, after landing in Kangerlussuaq, Chris published this WordPress sight with the name, SAGE.

Three days ago, with Summit Station in sight, Chris draws our route on the patch Mike sewed (with needle and suture from the Medical Kit!)

Science projects, field campaigns, and research efforts ALWAYS have an acronym, ALWAYS have a round table meeting to carefully choose it, and ALWAYS have it in place well in advance for promotion, funding, and outreach. SAGE on the other hand, entirely homespun, hand created, and rather stubbornly hard fought, barely snuck under the wire with ours! Comically, with a name that would suggest a rather OPPOSITE scenario.

To our credit though, and presented for your amusement, is the one flurry of potential acronyms that Zoe, Nate, Chris, and I exchanged via e-mail way back in February (thinking that an appropriate one would surely take form, well in advance of departure). As Co-Principal Investigators, on this NSF Funded project, Zoe and Chris will publish papers with this acronym, be saying the name through microphones in front of conference room audiences, and have it feature prominently on their resumes… fertile ground for a hilarious exchange of ridiculous garbage suggestions (though a couple were quite earnest and nerdy)! I have sadly edited out the ones that really had us rolling around, but the PG versions will at least bring a smile. We would love any fun acronyms that you could create, ex. post facto, for the traverse!

“RaBIIS” Radiative Balance across Interior Ice Sheets

“AbSEnT” Absorption of Shortwave Energy in Traverse

“ABCDEFGH” About Black Carbon Demolishing Ephemeral Firn in Greenland, Hollah

“SIN” Sun and Ice in the North

“ABSTRACT” Absorption of Snow Traverse Researching Albedo and black Carbon Together

“TAG ALONG” Traverse Across Greenland for ALbedo Observations oN Greenland

“SAVAGE” Spectral Albedo Variability Across northern Greenland Expedition

“ICING” Integrated Climate study of Interior Northern Greenland

“MANHAUL” Measurement of Albedo in Northern HAlf of greenland Unsupported Largely

“CANNIBAL” Counter 1972 ANdeaN Incident via Better AnaLysis of risk

“FUELDROP” Firn Unification and ELemental carbon Devastation Research On snowPack

and my personal favorite (a suggestion from Nate):

SASQUATCH – Surface Albedo Snow Chemistry QUantified Along Traverse Coordinates, Hopefully

Nate really was a Sasquatch as it turned out, by summing up the number and dimension of snow pits that he dug, we figure the guy actually moved a little over 107 metric tons (235,400 lbs) of snow!

The trip was incredible for us. We laughed, worked, drove, slept, and snacked (!) harder than most would do in a years time. I was asked, when we returned, what it felt like to be exposed to the Greenland elements for such a long duration. The first thing that came to mind was, “It was like those welter weight Puerto Rican boxing matches you might catch on TV… nobody blocking, each just connecting a blurring barrage of punches. Us VS the Greenland Ice Sheet. The only reason we’re still standing is that the bell rang, because Lord know’s that Greenland’s not giving up that belt”. Another couple of days and who knows what piece of gear might have given up the ghost, not to mention, “no meat, no manpower!”. We came in at just about the perfect time on all accounts!

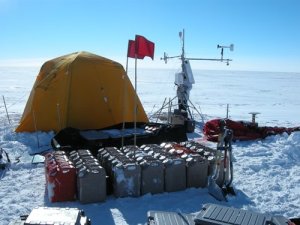

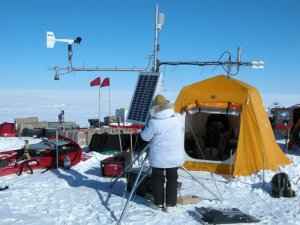

Nate, breaking the stow for one last time. This sled of empty fuel cans was warmly referred to as the “Crabber” for it’s resemblance to the burgeoning fully loaded Alaskan workhorse.

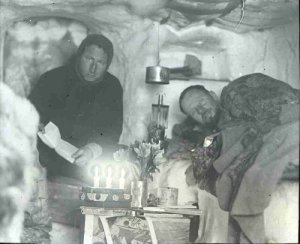

It’s been amazing to return here to Summit Station. The crew gave us a royal welcome home. Ken, the Station Manager, met us out on the snow and immediately jumped in the CAT 933 and dug a snow locker for our samples (at 8:30 PM). Inside the Big House, Trudy had set aside two full pizzas for our dinner, and a whole gang of friends came out to see us in. This is truly a wonderful group of people up here.

We have had a very difficult time being inside heated buildings! Down to t-shirts, bare feet, and with our pants rolled up we still can’t stop sweating! After these weeks and weeks of outdoor living and working we have become rather sasquatchy all around, entirely unfit for being near heaters!

With all the gear packed onto Air force pallets, our three snow machines parked, and the empty sleds piled up like Dixie cups, the Traverse has truly come to a close.

If you have ever done something grand, of wild proportions, of a scale that’s great enough where the start and the finish seem to have a lifetime between them- then you know the feeling the three of us share today.

And, if you ever find yourself drumming up plans to make a passage, attempt a crossing, or bid for a remote ascent- find men or women like Nate and Chris to fill out your team.

Steady, sound, inventive, adaptable, inspiring, and quick to laugh. These two never stopped working, never stopped making me smile, never stopped impressing me with their capabilities.

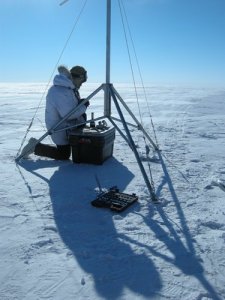

Chris’s view of Nate and I. He watched for our safety from this vantage point from the moment we started to the moment we parked the machines

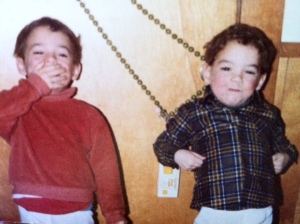

Nate harnessed up to man-haul the kitchen door off it’s hinges, something which clearly has me beside myself (we’re age 3 here)

An amazing dynamic can arise when certain personalities combine and set out from the beaten path. Some people truly rise and lead. I had two of them. Two Doctors who fill their days with a hundred other identities and talents, who are spectacularly funny, and a joy to spend time with.

I raise a glass to you Chris and Nate, you have spirits like a chip of ice: bright, hard, and pure. I would go to the very ends with you guys, just say the word. Thanks for the journey of a lifetime.